Allyson Pollock has reviewed Lord David Owen’s book ‘The Health of the Nation’ in the Lancet.

This article originally appeared in the Lancet, 28 March 2015.

In the history of the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), the Health and Social Care Act 2012 will go down as the most egregious act of vandalism against the people of England. During its passage through Parliament, David Owen called it the “Secretary of State’s Abdication Bill”, because the legislation removed the Secretary of State for Health’s responsibility for, and duty to provide, an NHS throughout England. The Act’s destructive effect is being felt in all political jurisdictions. But it has fallen to Owen, a peer in the House of Lords who describes himself as an independent social democrat, to take on the mantle of Nye Bevan, the founding father of the NHS. A veteran politician, Owen has served as Labour health minister and foreign secretary, and led the Social Democratic Party in the 1980s.

In the history of the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), the Health and Social Care Act 2012 will go down as the most egregious act of vandalism against the people of England. During its passage through Parliament, David Owen called it the “Secretary of State’s Abdication Bill”, because the legislation removed the Secretary of State for Health’s responsibility for, and duty to provide, an NHS throughout England. The Act’s destructive effect is being felt in all political jurisdictions. But it has fallen to Owen, a peer in the House of Lords who describes himself as an independent social democrat, to take on the mantle of Nye Bevan, the founding father of the NHS. A veteran politician, Owen has served as Labour health minister and foreign secretary, and led the Social Democratic Party in the 1980s.

In The Health of the Nation, Owen returns to grass roots politics in his account of the People’s Commission in Lewisham, south London, and the Save Our Surgeries campaigns to stop NHS hospital and general practice closures in 2013–14. He documents the tenacity of local campaigners and NHS staff and patients to stop closures of their hospital and community services, which were driven by the high costs of servicing private finance initiative (PFI) debt. The fight went to the High Court where the people won; they won again when the UK Government appealed against the decision. Owen explains how the costs of the PFI debt repayments combined with budget cuts are the engine for NHS hospital, general practice, and community closures across the country. He outlines how privatisation is opening up health services to international markets and making public services vulnerable to trade treaties and legal challenges from multinational investors. As a former doctor, he fears the dismantling of the NHS will see a return to public health tragedies on a scale not seen since before World War 2.

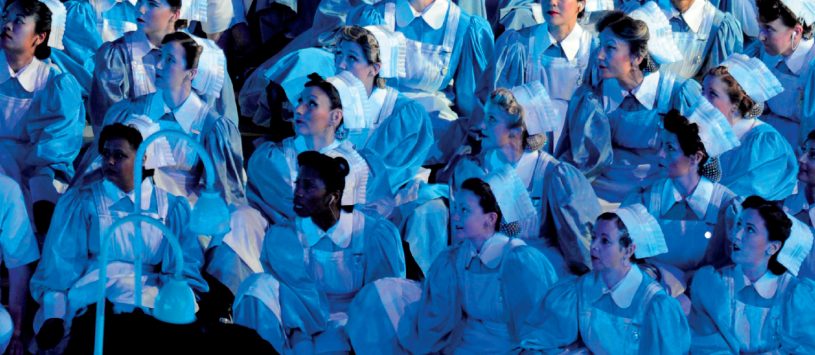

Values of social solidarity led to the creation of the NHS in 1948. At a time when the country was bankrupted by war, the nation decided to build a welfare state of which the NHS was a part. Moral values translated into a legal duty on the Secretary of State for Health to provide an NHS throughout the UK. It would be afforded because it was what the people wanted and voted for. The NHS was not a romantic aspiration.

The NHS survived in England until 2012. Since then, the NHS in England has been reduced to uncoordinated, fragmented services, disconnected from local communities and resident areas. The NHS is still in place in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, and for the people of the UK it remains the most popular of all the welfare institutions.

Owen sets out starkly how the NHS in England is withering away. By abolishing the legal duty to provide an NHS and entrenching market contracting and competition, the Coalition Government has reduced the NHS to little more than a public funding stream. In its place are market bodies, known as NHS England, Monitor, Care Quality Commission, and Clinical Commissioning Groups. Health services in England are moving to a US model in which increasingly access will not be through automatic entitlement but through local eligibility criteria as commissioners decide what services will be funded by the NHS and what will be paid for. For the first time since the NHS began, legislation requires health-care providers to draw up eligibility criteria as part of their licence conditions. In this system patient choice does not mean patients having choice of providers, but rather providers being able to choose their patients and treatments on the basis of ability to pay. Patients can and are being turned away and denied care.

The NHS had solid foundations. Its system was based on fairness of funding through income taxes and designed to maximise redistribution of resources and services. An efficient public bureaucracy ensured that administration costs were no more than 5% of the total budget and health expenditure didn’t rise much above 4% of GDP. However, since 1990, under Conservative and Labour administrations, market incrementalism has been a hallmark of NHS legislation with the introduction of the purchaser-provider split, use of private finance for new capital projects, and greater use of the private sector and market contracting. The incoming Labour Government in 1997 accelerated market-driven measures giving powers to Trusts to raise capital, use their financial freedoms to generate private income, and enter into exorbitant PFI debt obligations and commercial contracts. The link between planned services and the needs of the local population was being broken. And now, under the Health and Social Care Act 2012, all NHS Trusts must become NHS Foundation Trusts and legislation sets out that it expects these, in turn, to be 51% NHS and 49% private in terms of the income and services provided.

The destructive disorganisation that has resulted from the 2012 Act has led to enormous fragmentation and cost as general practice, hospital, and mental health services are broken up in piecemeal fashion and put out to tender with no regard to planning for need. Commercial contracting is expensive and reduces integration as providers are risk averse and cherry pick the best services and patients. Risk selection is accelerated by the carve up of many public health functions and transfer of some services, including children’s services, sexual health services, and district nursing, to cash-strapped local authorities that will in the future contract them out further fragmenting services. The UK Government is already being subject to challenges from the private sector when they perceive EU competition and procurement rules are not being followed. As Owen so passionately argues, abolishing the purchaser-provider split and the market in the NHS and returning services to public control and direct provision would protect the NHS from challenges from investors under TTIP and other trade treaties; it will also enable greater integration of health and social care and ensure equity of access and quality.

Owen warns us that we have little time left to reinstate the NHS—if we don’t, by 2020 the NHS as we know it will have disappeared not with a bang but with a whimper. Political pledges and manifestos cannot be trusted, solutions are required. Only legislation can reinstate the NHS. The UK election in May could well see a hung Parliament in which minority parties, such as the Scottish National Party, determine the balance of power. If this should happen the electorate will need to know that legislation to reinstate the NHS is not negotiable when deals are being struck.

On March 11, 2015, a Bill to reinstate the NHS in England was tabled in Parliament with cross-party support. The NHS Bill 2015 will abolish market and NHS contracting and the expensive market bureaucracy, make the Treasury responsible for resolving the high cost of private finance, and restore the duty of the Secretary of State to provide listed health services to meet the needs of people throughout England. Prospective parliamentary candidates are being asked to declare their support for this Bill before the election.

Politicians declare we can no longer afford universal health care, although the cost of the NHS per person is far less than any country with marketised health systems. The UK certainly cannot afford a market—the US experience tells us what is in store with health-care costs in excess of 17% of GDP. Owen calls on us to ask our prospective parliamentary candidates to support legislation to restore and reinstate the English NHS in the next Parliament, in return for their votes. If they do not the NHS will wither away as large for-profit multinational corporations take over patient services and determine what will be paid for and what services will be provided. Inequity and denial of care will become the new hallmark of health services in England.

The Health of the Nation is a clarion call from an experienced statesman to aspiring politicians across the political spectrum. Owen is writing for posterity. The question on May 7 is how do the politicians want to be remembered, as the architects or destroyers of the NHS?